Making connections between farmers and farm law is critical. Farmers are affected by law and policy, and they have the right to know how. Farm Commons is an organization fostering discussion between farmers and attorneys and connecting farmers with the law to help them understand how it affects their operation and build a strong legal foundation for their farm. By providing sustainable farmers in particular with proactive legal resources, Farm Commons’ mission is to create stable, resilient foundations of community based food systems. The website links to farm law resources and even a short video series on specific farm law topics. Check it out!

2018 Decrease in Net Farm Income

The USDA's Economic Research Service (ERS) publishes reports explaining indicators of economic performance for the U.S. farm sector and farm businesses. Stakeholders can use these analyses to inform their perspective on the financial health of the U.S. agricultural economy.

The program’s forecast of 2018 farm income exposes a projected decrease in both net farm income and net cash farm income. Net cash farm income includes “cash receipts from farming as well as farm-related income (including government payments),” but net farm income is “a more comprehensive measure that incorporates non-cash items.” After an increase in 2017, they were both expected to decline this year. This may be due to the increase in production expenses, calculated to be 3.3% more than 2017, 1.2% after inflation adjustment. Since 2013, net farm income has been on a declining trend, but this year’s projections are certainly not on par with last year’s spike.

Industrial Agriculture and a Call for a Paradigm Shift

An abundance of publicly available, credible evidence establishes that the current industrial, high input, high externality agricultural system in the U.S. hurts consumers, the natural environment, and the food security of today and the future. This evidence suggests that sustainable and agroecological alternatives are viable, but the U.S. has yet to respond on a large political scale.

In an academic paper I wrote during an International Food and Agricultural Politics course I took last year at American University, I explore explanations for this phenomenon. I address the mainstream explanation of the issue of influence from big agribusiness corporations on politics and the market, and I offer an ideological theory—an explanation for the mainstream explanation. I propose that the true reason behind the lack of large-scale response is a path dependency in the American capitalist paradigm, and I argue that there is a deeper level than politics to be examined: a cultural-philosophical level from which stems the potential for a paradigm shift and widespread social and political change.

I hope it leads you into your own exploration of food and agriculture in the American psyche and how we can shift the paradigm to promise the future of sustainable agriculture.

Reconnecting with Our Food

Do Americans feel connected to farmers and food? With the increasing industrialization and consolidation of agriculture in the U.S. and globally, American consumers are getting further and further away from their food — physically, psychologically and emotionally.

Efforts like the farm to table movement, farmers markets, community gardens and foodie culture are moving in the right direction to create more understanding for consumers and connect them to the source of their food, but there’s always room for improvement, especially in a time when the ingrained norms of our food system are working to keep us disconnected.

What do we know about where our food comes from?

An online survey commissioned by the Innovation Center of U.S. Dairy last year found a frighteningly low level of “agricultural literacy” among Americans: 16 million people thought that chocolate milk comes from brown cows, 40% of California 4th, 5th and 6th graders didn't know that hamburgers come from cows, orange juice was the nation's most popular "fruit," and french fries and potato chips were the nation's most popular "vegetables.”

The 2017 Michigan State University Food Literacy Poll also exposed an overwhelming disconnect between Americans and their food. The question, “How often do you seek information about where your food was grown and how it was produced?” exposed that 35% of the people surveyed rarely look into where their food comes from, and 13% never do.

“How often do you seek information about where your food was grown and how it was produced?”

2017 Michigan State University Food Literacy Poll

In 2011, two national surveys by the U.S. Farmers & Ranchers Alliance’s (USFRA) Food Dialogues project collected data on opinions, attitudes and questions consumers and farmers and ranchers have about the current and future state of how food is grown and raised in the U.S.; the results revealed that “lack of access to information, as well as no interest or passion for the topic, have divided consumer opinion on the direction of agriculture.” But interestingly, while 72% of consumers identified as knowing “nothing or very little about farming or ranching,” 69% of them think about food production "at least “somewhat often.” So even where there is interest in knowing where food comes from, there still seem to be barriers preventing consumers from finding out.

When asked about their impressions of consumers, 86% of farmers and ranchers responded that “the average consumer has little to no knowledge about modern farming and ranching,” and 58% felt that “consumers have a completely inaccurate perception of farming and ranching.” Their top priorities for what they want consumers to better understand are: 1) the effect of pesticides, fertilizers and antibiotics on food, 2) where food comes from in general, 3) proper care of livestock and poultry, 4) the effect of government regulations on farming and ranching, and 5) the economic value of agriculture.

Additionally, what few Americans know about farmers is that “working two jobs is almost a requirement to farm” and that while “the average farmer usually owns land and other assets, most of which are necessary for production,” she also “requires non-farming income to make the farming operation work successfully.”

Where are the missing connections?

It’s clear that many Americans don’t know about what or who is involved in the production of their food. But why is that? One obvious explanation is that only 2% of the country works in farming, so that leaves 98% of the country to find information about it out of their own volition Since the rise of processed food and agricultural industrialization, each American farmer has had to feed so many more people, now that there are less farmers.

Source: USDA

The amount of processing and travel that our food goes through before it gets to us also explains why we feel detached from it: it somehow just shows up in our grocery stores after flying sometimes thousands of miles from an unnamed farm across the country or the world.

Why should we know or care where our food comes from anyway? And why does it matter who’s growing our food? From a health-centric perspective, it’s always important to know what we’re putting in our bodies. But from a broader perspective of social and environmental justice, knowing who grows our food and where it comes from allows us to better understand the consequences of our food purchases — on farmers, animals, and the environment. If we understand the process of producing something, we can understand its impacts and therefore our own impacts as consumers of it. Take beef for example: if we understand the inputs and environmental impact of raising beef, and even the different practices of various producers, that might influence which brand of beef we buy or whether we buy it at all. And for seasonal produce, learning about its production will allow us to make more informed decisions about when we buy them.

On top of all that, having more of an understanding of food production and farmers lives allows us to feel more connected to farmers, making farm policy feel more relevant and better enabling and encouraging us to be advocates in the realm of farm policy.

But making these new connections will require some ideological shifts… The crux of connecting with food is breaking through the impasses we’ve constructed with dichotomies: farmer vs. non farmer and urban vs. rural. We view these as total opposites, which creates a sense of “other” and acts as a barrier to understanding and connecting with each other and our food.

The farmer vs. non-farmer disconnect is exhibited by the low levels of food and agricultural literacy of the average American consumer. Even the concept of farmer and non-farmer responsibility to each other (the theme of this blog page) assumes a dichotomy, but the goal of this page is to help connect non-farmers to farmers rather than continue keeping them separate like the current industrial system does, with food production so far away from consumers on levels of both physicality and understanding.

Urban and rural landscapes, cultures, and communities are largely seen as opposites, with suburbs as a middle ground. Possibly due to their lack of interaction, there is a disconnect between their beliefs about each other. According to a Pew study, the majority of people in each type of community don’t believe that other communities understand their problems, but they think they understand the problems of other communities…

What communities believe about other communities:

What communities believe about themselves:

The study also revealed that rural and urban communities feel that the other doesn’t understand their values. This perceived lack of understanding between urban and rural communities is problematic because in reality they are connected and interdependent on many levels including food production and consumption as well as economics and politics. But the dichotomization and ideological separation of urban and rural limit their exposure to one another with an “out of sight, out of reach” mindset and perpetuate the perception that they have nothing in common and no effect on each other. The belief on behalf of rural communities that urban communities don’t understand them has the potential to make rural communities feel isolated and alienated, and this lack of understanding and connection might be a major barrier to urban involvement in farm policy and mainstream incorporation of rural politics.

In order to break the dichotomy between urban and rural, we need to explore the need for a new ethos development: an ethos that sees urban and rural as connected communities and focuses on their common goals about the future of agriculture and the American relationship to food and its production. Already, there are are well-meaning urban initiatives, but they could go one step further in establishing a broader ethos. They are connecting people to food but not necessarily to farmers.

Where do we already connect with food and farmers?

Farm to table

The farm to table movement brands itself on locally sourced ingredients, often organic, in response to the “processed food empire.” More and more restaurants are joining the trend, sometimes identifying as “farm-to-fork.” The principles behind it are mainly food security, proximity of food production to consumption, self reliance, and sustainability. The movement, along with the increasing demand for locally sourced groceries and farmers markets, came at the same time as the most recent American environmental and climate awakening, which makes sense since eating local avoids some of the environmental impacts that come along with buying into the industrialized, globalized food industry. (Learn more about the history of the farm to table movement here.)

Farmers markets

Farmers markets are on the rise, bringing us closer to the source of our food: we interact with farmers and take out the grocery middleman, we experience buying food in its more natural form rather than the processed and perfect state we find it in at the grocery store, we feel a more direct effect on farmers with our purchases, we get to ask questions about foods from the most expert sources, and we enjoy the environmental benefits of shopping locally and seasonally.

But on the other hand, this romantic Sunday morning glimpse of farmers and their products leaves out some of the realities of rural life. We must think critically about how farmers markets are creating both intended and unintended effects. Are farmers markets truly an appreciation for and integration of rural life, or are they an appropriation of it? Are customers really understanding new things about their food and paying attention to where it came from or simply going from stand to stand treating it like nothing more than an outdoor grocery store?

For example, at the Dupont Market in Washington, D.C. (where I shop weekly), farmers drive from Maryland, Virginia and Pennsylvania to set up their stands, but it often appears that market-goers float from stand to stand without acknowledging which state they’re shopping from. Vendors at the market are eager to answer questions about their products, and this weekly social fusion is the perfect setting for non-farmers to learn more about where the food they’re buying is coming from and who’s growing it. Farmers markets are an essential component in making new connections between farmer and non-farmer and between urban and rural, and it certainly shows progress in consumer attitudes that farmers markets are becoming more popular, but we should make sure we’re building meaningful relations with local farmers when we go.

Community gardens

Urban community gardens are a great way to engage with agriculture and food education, develop a sense of self-sufficiency and fulfillment, attain food security, build community, and increase green space in cities. No matter what their reason, everyone can get something out of working in a community garden.

One way to look at community gardens in cities is creating a connection with farmers through incorporating food cultivation and land stewardship into our own urban lives and gaining a better understanding of agricultural processes.

But is there a chance that rather than (or in addition to) connecting with farmers, community gardens are replacing them? Gardening for personal use or for hobby doesn’t help us understand the economic struggles of production contracts and pressure for high output that many professional farmers experience. While becoming self sufficient through community gardens, we become less dependent on farmers and further distance ourselves, maybe even feeling even more separate from rural and farmer communities and their relevant policy…

Of course, community gardens are an important component for food security in vulnerable urban populations and useful for urban food and agricultural literacy in general. But we have to make sure we’re using our gardening experience and urban garden development to connect with farmers and rural communities as a way of breaking the urban-rural dichotomy, rather than perpetuating it.

Foodie culture

“Foodies” and food bloggers are a trendy new group of people who care about good food, emphasizing the importance of sustainable, organic and local food rather than mass produced commodities. Foodie culture consists of posting food experiences on social media, whether it be at a restaurant, food truck, or home-cooked meal. Food Instagram accounts and blogs portray beautiful and model quality photos of food, making something as simple as an ice cream cone or french fries look like a delicacy. Restaurants also play a role in foodie culture, as many of the trendy farm to table and sustainable restaurants provide an experience of food that aligns with foodie values.

In terms of the American consumer’s connection to food, foodies might be considered in good shape since they’re in touch with what they’re eating and appreciate ingredients. But the movement also carries a sense of elitism. It can appropriate where ingredients come from by turning quality food into an elitist trend and portraying food appreciation as an exclusive and expensive hobby. Foodies can afford to pay for the fancy, fresh, specialty ingredients they’re recommending on their posts, but not all their social media followers can. They also may be considered elitist because of the way they portray an essence of knowing more than their followers: they know “everything related to food, whether it be where the good restaurants are, which places have the best lunch deals, which chefs are leaving which restaurants and which chefs are opening a new restaurant, and so on.”

Foodie culture is a rapidly rising trend in the U.S., and foodies love specialty foods, especially chocolate, oils, cheese, and yogurt and kefir. According to the National Association for the Specialty Food Trade (NAFST), Package Facts and the 2012 Culinary Visions Panel Survey, “76% of U.S. adults enjoy talking about new or interesting foods, 53% of U.S. adults regularly watch a cooking show, and 68% of adults purchase specialty foods for everyday home meals.” Foodies’ obsession with speciality foods symbolizes that they can afford these kinds of expensive luxuries, contributing to the elitist nature of the trend.

Specialty olive oils on tap at artisanal oil and vinegar shop Stagecoach Olive Oil & Vinegar Co. in Stamford, Connecticut.

If foodies adjust the movement to connect to food in a more affordable and accessible way, it might become an avenue for the rest of American consumers to connect to food as well. It may also consider tying more of an explicit connection to farmers into its rhetoric. Many foodies already promote shopping local and supporting farmers markets, and because of the ability to impact culture that the movement has exhibited so far, it may be able to spread political awareness of issues around food production and farmers. So with the potential for more intentional incorporation of farmer-non-farmer connections, foodie culture is an important avenue of change to keep an eye on.

Where do we go from here?

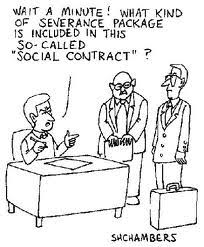

This new ethos American consumers need in order to better relate to farmers and where our food comes from is connected to a new social contract between farmer and non-farmer that will enable non-farmers and urban communities to increase our understanding of farming and rural life and break down the dichotomies between farmer and non-farmer and urban and rural, make the existing initiatives as productive and effective as possible in spreading a message of connection, and apply our new set of values to use our political support and food shopping choices to better serve farmers.

Farming is a public service.

The concept of farming as a “public service” or “public good” has recently become a hot topic of conversation on justifying supportive farm policy. But the first thing to understand is what these terms mean. A public good, in an economic frame, is a good which nobody is excluded from using, and of which use by one individual does not prevent any others from accessing or using it. A public service service is a government-provided service for people living within its jurisdiction, be it directly (like infrastructure or education) or indirectly (through financing a service).

Applying the public good “concept,” farming should be considered one simply for its land stewardship (the natural environment being a public good) but also for its service to the American public through food production. Already, the American government unconsciously recognizes farming as a public through providing agricultural subsidies: “in the context of agricultural subsidies,” a public good “refers to non-commercial benefits that are determined through democratic processes to be in the public interest.” If farming is enough of a public good to warrant publicly funded subsidies, it warrants support mechanisms for farmers beyond promoting commodity crops.

The idea of farming as a public good isn’t new; it was even discussed in social contract theory by philosopher Thomas Hobbes. Social contract theory proposes that a government is responsible for supporting and protecting public goods as part of the social contract, and since farming requires social cooperation and therefore a social contract, it is a public good and should be protected as such by policy. (For a deeper analysis of farming as part of the social contract, check out this previous blog.)

National Young Farmers Coalition (NYFC) is a national network of thousands of young farmers, ranchers, and consumers working to promote the concept of farming as a public service. (Check out NYFC blog posts tagged with “farming is a public service.”) The organization’s 2015 “Farming is a Public Service!” report presses the need for new and young farmers, explains the obstacle of student debt, and calls for federal loan forgiveness for new farmers under the Public Service Loan Forgiveness Program.

The report brings to light that America is in desperate need of young farmers: between 2007 and 2012, the number of farm operators dropped by 90,000, and the average age of the American farmer increased to 58. When these farmers are gone, who will grow our food?

According to NYFC, student loan debt is a major obstacle holding young Americans back from entering farming and maintaining successful agricultural careers. In a survey of 700 NYFC members and supporters with student loan debt, 53% reported that they are “currently farming but struggle to make their student loan payments on a farm income,” and almost 30% “didn’t pursue farming or are waiting to pursue farming because their student loan payments are more than a farming salary would support.”

The report suggests that in the same way the government incentives Americans to enter medicine, education, and other public service careers, it should encourage young Americans to make careers in agriculture as well, and the Public Service Loan Forgiveness Program offers an avenue for that.

The program “helps Americans enter professions that provide a public good but have salaries too limited at the outset to manage student loan debt,” and NYFC provides strong justification for new farmers to be included. First, “agriculture meets one of our most basic needs—producing the food we eat.” Second, “farmers manage and steward almost a billion acres of land, which is about half of the land area of the U.S.,” and thirdly, “farmers support rural economies, providing jobs and income.” But so far the program only considers farming a public good in New York and Wisconsin. NYFC is pushing to make it reach wider and urging Congress to extend the program to farmers nationwide.

The organization is also pushing for the Young Farmers Success Act, under which “a farmer would see the balance of his or her student loans forgiven after making 10 years of income-based student loan payments, freeing capital for farmers to acquire land and equipment.”

Supporters of the Young Farmer Success Act including the NYFC, led by farmer Lindsey Lusher Shute of Clermont, NY.

Aside from NYFC, Roots of Change, a “think and do” tank for sustainable food systems, has worked on the idea for a renewed social contract that treats farming as a public good and advocates for fair policy support as such.

Another rich resource identifying farming as a public good or service is the recent report “Hope from the Heartland,” which looks into how to bring more rural representation to Washington and how the Democratic party can better serve the American Midwest (or heartland). The report points out that the party is in a period of lower-than-ever support and identifies problems in it that alienate rural communities and farmers in the heartland.

Aerial view of Midwestern farmland.

Research for the report consisted of interviewing local officials in rural, Midwestern states that feel forgotten and overlooked by both Democratic and Republican parties and that their Democratic representatives only talk about issues irrelevant to rural and agricultural communities. The results from these interviews offer valuable suggestions for improvement in the party’s policy on and inclusion of rural and agricultural issues. Major emerging viewpoint were that Democrats must stay focused on bread-and-butter issues, develop better communication tools to counter conservative media, and most importantly include more voices of rural constituencies who share broad democratic goals even if they disagree on some social issues.

The report also identifies farming and agriculture as a main area where Democrats need more policy work. Interviewed for the project, Iowa State Senator Tod Bowman “traces the problems of Democrats to the farming culture and that they do not compete for farm votes.” The population of farmers, including part-time farmers is unique, complex, and is evidently misrepresented or underrepresented in Democratic politics.

Bowman points out that along with farm sizes shrinking due to consolidation, there is an increasing prevalence of part-time farmers (those who own fewer than 200 acres and those who rent out acreage). According to him, these farmers “may not be big landowners, but [they] still represent the farm culture of ‘looking at the bottom line, being more individualistic, and being averse to taxes and regulation.’” The takeaway from this discussion on the heartland farmers is that “no one talks to them” and that politicians need to reach out to more farmers and have more agricultural background and understanding in candidates.

President Barack Obama touring a field with California farmer Joe Del Bosque and his wife Maria in 2014 in response to one of California’s worst droughts in over 100 years.

Since farming is supported by the government (as a public service), it makes sense that farmers should have representation in shaping the policy that affects them. But whether it be through bringing farmers from the heartland to Washington or bringing recent college graduates into farming through the Public Service Loan Forgiveness Program, the public sector has a duty to serve farmers just as farmers serve the public.

Farming is clearly a public good and it’s time we manifest it as such in both American policies and attitudes. Rather than think of farming as an industry to produce cheap commodities, it’s time we get back to seeing farming for what it truly is… A public service cultivating healthy communities and land. The heart of local and national economies. Foundation. Stewardship. Livelihood.

A Brief History of U.S. Farm Aid

This Wall Street Journal article goes over a brief history of U.S. farm aid from before the Great Depression to controversial farm policy under the Trump Administration. Sparked by a policy change from this summer extending up to $12 billion in emergency aid to American farmers hurt by trade tariffs, the article examines the impact of past government spending towards farm support on agricultural trends and the U.S. economy. To understand contemporary farm aid, it’s important to know how government spending on farms affected the country in the past. Sign into your Wall Street Journal account or read an excerpt here:

How Farm Aid Became a Fixture

Trump administration’s plan for $12 billion in help for farmers hit by tariffs builds on a history of agricultural support

By Jacob Bunge

An Oklahoma farmer in 1936 battles rising dust. Many farm-aid programs were put in place in the 1930s to provide temporary assistance. PHOTO: LIBRARY OF CONGRESS

The U.S. government has been spending directly on agricultural-support programs ever since the Great Depression.

This week the Trump administration said it would extend up to $12 billion in emergency aid to farmers hurt by trade tariffs. That comes on top of about $21.5 billion the government is already expected to spend this year on existing farm-support programs, according to the Congressional Budget Office. Those existing programs are meant to shield farmers from crop-price downdrafts, help young farmers get started and encourage conservation.

Most of these [programs] were put in place in the 1930s originally as temporary programs, said Joseph Glauber, a visiting fellow at the American Enterprise Institute and a former chief economist for the U.S. Department of Agriculture. Here we are, however many years later, and they’re ingrained.

Over the century following the country’s founding, the U.S. government supported agricultural production through steps such as public land sales and establishing the land-grant university system, which pursues regional crop research. Government spending also funded early irrigation and drainage projects that boosted agricultural output.

It worked in some cases, too well. American farmers expanding harvests helped pushed down crop prices in the years leading up to the Great Depression, prompting the government to look at national-level farm support programs. The 1933 Agricultural Adjustment Act, part of the Depression-era New Deal, introduced government price supports, paying farmers to leave grain and cotton fields idle and shrink hog herds. The government also purchased farm goods and subsidized export sales. Farm incomes improved, but the U.S. agricultural sector didn’t fully recover until World War II jump-started demand.

Farmers and supporters rally in 1983 in Iowa, seeking price supports for crops and a moratorium on farm foreclosures. PHOTO: BETTMANN ARCHIVE

To help stave off a postwar recession, Congress extended farm-support programs, in the process making government support the norm in farm country. Subsequent wars and growing exports whittled down food surpluses, but also gave farmers in other countries an incentive to grow bigger crops. In the early 1980s, rising interest rates, President Jimmy Carter’s grain embargo against the Soviet Union, and bad weather combined to push a wave of farms into foreclosure, leading Congress in 1985 to set out a new loan-based price-support system.

The Farm Belt recovered, and by the mid-1990s Congress sought a way to wean the sector from government support. The 1996 Farm Act eliminated most controls on supply and devised a new system of fixed payments related to past production levels, meant to last five years. But soon, a string of bumper harvests and the 1998 Asian credit crisis pressured crop prices and posed a new threat to U.S. farmers' livelihoods, spurring the government to make periodic payments to mitigate losses. The 2002 Farm Act converted those payments into a program that paid farmers when commodity prices dipped below specified targets.

By 2014, growing criticism of direct payments to farmers by then averaging $6.6 billion annually, regardless of crop prices or farm incomes led Congress to replace these with a new insurance-based system. That system, currently in effect, includes broadened crop-insurance coverage, a supplemental program that compensates out-of-pocket losses not covered by insurance, and assistance when farmers’ revenue or crop prices fall below certain levels.

Films on the Future of Farming

Farmers for America

As its creators describe it, “the documentary traces the extraordinary changes coming to America’s food system as more and more consumers flock to farmers’ markets, embrace farm-to-table lifestyles and insist on knowing where their food is coming from. At the center of the film are the farmers, young and old, who provide the spirit and energy to bring urban and rural America together over what both share in common: our food. These farmers reflect nothing less than the face of America. With the average age of today’s farmer at 60, and rural America losing population as the cost of land and equipment soars, this film reveals the people waiting to take their place, the practices they’re championing and the obstacles they must overcome.”

So check out the captivating and informative film by Farmers for America taking a deep dive into the future of American farming. Private screening options include buying community, conference or educational licenses; otherwise, there are occasional public screenings. Upcoming screenings are in Keene, New Hampshire, Washington, D.C., Pepin, Wisconsin, and Louisville, Kentucky, but look on the website for more screenings around the country!

2. Farmland

This documentary by award-winning director, James Moll, exposes the lives of American farmers and ranchers in their 20s running their own farm businesses. Most Americans have never stepped foot on a farm or ranch or even talked to the people who grow and raise the food we eat, and Farmland offers a new perspective on the changing norms of family farms and challenges and rewards of being a young farmer today in America. The narrative of young farmers is a crucial one in today’s conversations about American farm politics, so check out the website to see all the online viewing options and instructions.

3. Dolores

When talking about farms, we cannot leave farmworkers out of the conversation. They are responsible for all of the labor that goes into our food, and they are being abused. This documentary about Dolores Huerta exposes her life of activism for farm laborers. “Dolores Huerta is among the most important, yet least known, activists in American history. An equal partner in co-founding the first farm workers unions with Cesar Chavez, her enormous contributions have gone largely unrecognized. Dolores tirelessly led the fight for racial and labor justice, becoming one of the most defiant feminists of the twentieth century.” Watch the trailer above, where you can also rent or buy the full documentary online.

4. food Chains

Everyone who eats is involved in the food chain. But most of the chain is hidden from us: the conditions for the people who grow and pick our food, the process of distribution, and the institutions that hold the power of change. This documentary connects consumers to the food system, explores the disproportional power of supermarkets and the fast food industry, and tells the brave stories of abused farmworkers and their fights for justice, including the Coalition of Immokalee Workers and its hunger strike for the Fair Food Program to eradicate abuse of tomato pickers.

The Social Contract Between Farmer and Non-Farmer

Is there a social contract between U.S. farmer and non-farmer today? Is it being fulfilled?

Social contract theory

According to Enlightenment philosopher Thomas Hobbes, humans begin in “the state of nature,” a state before civil society, without order or government. Social contract theory is the model in which people in the state of nature surrender some of their freedoms and submit to the majority rule and authority of a government. In exchange, that government protects the natural rights of the people. The government creates laws to protect the people’s rights, and the people are expected to obey those laws. The theory suggests that each individual of the public will voluntarily submit to the social contract because it is to their own advantage. By being a member of society, everyone is implicitly signing this invisible contract.

What does this have to do with farming?

Now instead of a contract between people and a government, let’s think about a contract between farmer and non-farmer, producer of food and consumer of food, steward of the land and citizen of the land. In this case, one end of the contract is the farmer, and the other end is not only the people at large, but also the government and the institutions of civil society.

When Hobbes describes the state of nature, farming does not exist because it requires social cooperation and therefore a social contract. He explicitly labels farming as “a social good,” something guaranteed by the social contract and a concept I will explore in another post about farming as a public good. Hobbes’ assumption makes sense: since the production of food is crucial for an organized society, and since it requires political infrastructure and support, it certainly would fall under the terms of the social contract and even warrants one of its own.

terms of the contract

First, let’s look at what’s expected of farmers. The obvious one is food. Non-farmers in the U.S. (98% of the population) depend on someone else (the farmer) to grow their food.

Next, non-farmers expect environmental stewardship by farmers. According to the theory, protection of the environment is part of the original social contract, and applying that idea to this new social contract in the wake of climate change, environmental expectations of farmers may be higher than ever. Non-farmers expect farmers to produce healthy and wholesome food, use safe and moral practices (guaranteeing animal’s rights and fair treatment, etc.), and solve climate change all at once. It’s true that farmers hold a lot of power to make environmental changes. They are stewards through caring for the soil and its microorganisms, promoting biodiversity and agrobiodiversity, managing their water consumption, mitigating water contamination, reducing agricultural emissions, and so on. But they can only utilize this power given sufficient resources, in other words, if non-farmers keep their end of the contract as well.

So what are non-farmers responsible for? In line with the expectation of farmers to grow food, the non-farmers are expected to buy food. Farmers depend on non-farmers to support them financially through buying what they grow. And depending on the farmer, they may expect more than just buying food; they may want the non-farmer to appreciate the food as well (appreciate its quality or purity or the care that went into growing it).

But if non-farmers expect ethical commitments from farmers (environmentally sustainable practices, moral animal treatment, non-toxic food, etc.), then non-farmers are responsible for more complex commitments too. These include political and social support for farmers, governmental financial assistance where needed, infrastructure and reliable markets, and more ethical responsibilities such as seeking to understand farmers’ needs and advocating for farmers’ rights. On a more intimate level, farmers expect non-farmers’ “help rethinking and preserving their livelihood,” because while it may feel like a simple business exchange for non-farmers when they buy food, it’s often much more than that for the farmer growing the food: it is her livelihood.

Are both parties meeting the terms?

Loaded question, I know. But there are certainly ways we can get a sense. The fact that there are so few new farmers may be a sign that the contract is not being met by non-farmers in a way that makes farming attractive right now, that non-farmer society has created inhospitable conditions for new farmers. For example, lack of land access is the number one barrier for new farmers; land is too expensive for young farmers who want to get into the field, and there’s not enough policy supporting them, which is scary considering they are the future of American agriculture.

Aside from low land accessibility, the industrialized business model of food has degraded agriculture to a source of cheap food: it is no longer seen for its fundamental role in society. Roots of Change, an organization working in the sustainable food movement, discusses this concept in a thoughtful and comprehensive article designing a new social contract between agriculture and the public. Their analysis suggests that this reduction of agriculture threatens civilization itself, since it is so foundational. Their version of the social contract has 10 terms, most of which set expectations for the farmer, notably the environmental responsibilities of the farmer. This contract sees today’s growing environmental crisis as an opportunity for farming to become a fundamental characteristic in the nation’s identity again. And the growing “good food movement” in recent years is progress in the right direction.

While the expectations set for farmers in the contract might seem too demanding and unrealistic, they also might be a positive change agent by bringing agriculture back to the center of everything. According to Roots of Change, seeing agriculture “as a primary solution to many problems faced today creates the basis for a new social contract.” And a new social contract for farming is exactly what the U.S. needs. Roots of Change sees this new contract as one that stops defining agricultural products as commodities, sees food as valuable (which means it shouldn’t be cheap, so farmers don’t have to externalize costs), and provides more financial support for farmers (especially to incentivize environmental health).

Where does the Farm Bill fit in?

Since the non-farmer population includes everyone that is not a farmer, we can look at the government and policymakers in particular and not just the public at large. That separation being made, it’s important to remember that the public also affects farm policy by voting, participating in civil society, influencing policymakers through activism, and acting as conscious consumers and eaters. In the new social contract, the non-farmer has the responsibility to support the farmer (therefore supporting society as a whole, since farmers are foundational) by working to improve the Farm Bill. A non-farmer may see the Farm Bill as irrelevant and distant public policy that affects someone far away on a farm, but it affects everyone, non-farmers included, so every American should care.

The Farm Bill is at the crux of the non-farmer’s end of the contract. If the non-farmer expects the farmer to meet all of the expectations set in the contract, then he needs to ensure that policy will support those expectations. Farm policy currently pays too little attention to small farmers and the environment, but farmers want to be environmental stewards; they just need the policy to support it and make it attainable, and that support has to come from non-farmers.

A Financial Contract

Earlier I mentioned a monetary component to the social contract between farmer and non-farmer: the farmer grows food and the non-farmer is expected to buy it, offering the farmer a dependable market. But when the non-farmer spends money on food, how much of it really goes to the farmer? Not as much as you’d probably expect… Only 7.8 cents of each consumer dollar actually goes to the producing farmer.

In addition to the social contract, farmers are also engaged in various legal contracts with non-farmers: production and marketing contracts through contract farming. In these kinds of contracts, a buyer makes a contract with a farmer to buy a certain amount of food that they will then sell to the public. While this is not a direct relationship between the farmer and the public, buyers are nevertheless non-farmers, and the public is connected down the line when it buys products that the buyer sourced from the farmer. With that in mind, members of the public can act as conscious consumers (otherwise known as political consumers), choosing to buy or not buy products from certain companies or sources based on their policies, ethics, and practices with the goal of changing industry norms.

At the end of the day…

We are all party to the social contract between farmer and non-farmer. And it is our civic duty as Americans and as eaters to support farmers. Through consumer behavior, policy, and civic engagement, non-farmers can make this new social contract the norm and give farmers the support they need to keep their end of the contract. If the current political situation with scarce support for farmers where they need it is the state of nature, let us all sign this new social contract. After all, as Hobbes would say, it’s for our own good.

U.S. Farm Trends: 1900—Today

How has farming developed since before the Industrial Revolution and the turn of the century? In addition to the monumental changes in the physical practice of farming that industrialization and mechanization allowed, the social and political implications of farming and farmers has also transformed in dangerous ways.

1. Industrialization pushed Americans out of the their rural lives and into the city for urban and industrial lives.

2. The size of farms increased while the number of farms shrunk.

3. The number of farmers shrunk so much that farmers now make up less than 2% of the U.S. population. With more farmers retiring than starting, agriculture is at at risk.

4. Today, most farms in U.S. are small family farms (which are ironically not the ones supported by policy). Family farms are owned or operated by families and often passed down through generations, but they can also be corporate owned or partnered with corporations.